From First- to Third-Generation EGFR-targeted Drugs: How Can Patients Understand Differences in Efficacy and Adverse Effects?

Epidermal growth factor receptor EGFR–targeted drugs represent a cornerstone in the treatment of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring EGFR gene mutations. EGFR mutations are a major category of lung cancer biomarkers.

NSCLC is the most common subtype of lung malignancy, accounting for approximately 85% of cases, and the majority of patients are diagnosed at a locally advanced or metastatic stage.

EGFR-targeted drugs exert their antitumor effects by precisely inhibiting the EGFR signaling pathway, thereby blocking abnormal tumor cell proliferation.

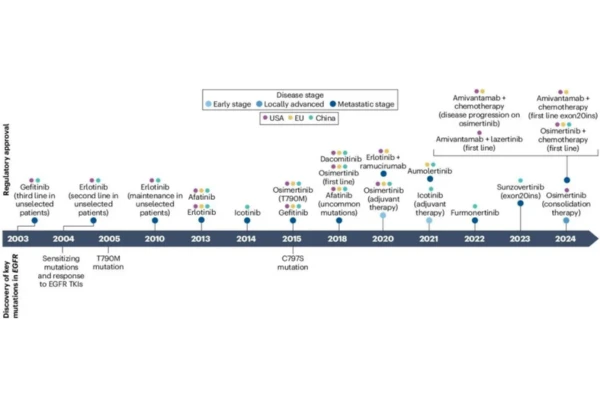

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) have undergone three generations of development, with progressive improvements in efficacy and safety, providing individualized treatment options for patients with EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC.

Commonly used agents include first-generation gefitinib, erlotinib, and icotinib; second-generation afatinib and dacomitinib; and third-generation osimertinib and aumolertinib.

These agents differ significantly in mechanisms of action, efficacy profiles, and adverse event spectra. Hong Kong DengyueMed will provide a professional and systematic analysis of the efficacy and safety differences among the various generations of EGFR-TKIs.

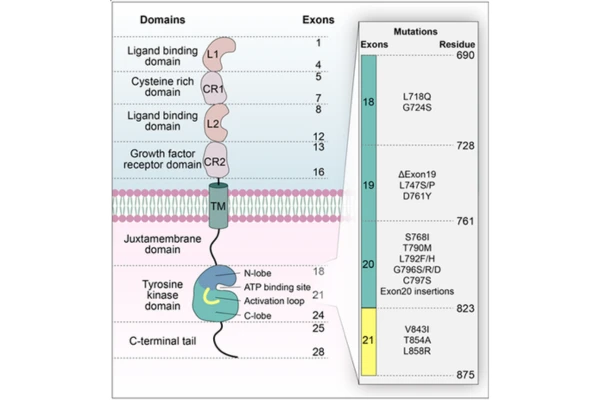

What Is EGFR?

EGFR is a transmembrane glycoprotein. Its extracellular domain consists of four subdomains (I, II, III, and IV), of which domains I and III are responsible for ligand binding (e.g., epidermal growth factor), while domain II participates in receptor dimerization.

The intracellular portion contains the tyrosine kinase domain, which comprises the N-lobe, ATP-binding site, activation loop, and C-lobe. The ATP-binding site is the key binding site for EGFR-TKIs.

EGFR is a critical regulator of cellular signal transduction, and its aberrant activation is closely associated with oncogenesis. Inhibition of the EGFR signaling pathway via targeted agents has become an essential strategy in precision oncology. Below is a systematic introduction to first- through third-generation EGFR-targeted drugs and their similarities and differences.

First-Generation EGFR-TKIs: Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Icotinib — The “Foundation Drugs” of Targeted Therapy

First-generation EGFR-TKIs were the earliest EGFR-targeted drugs introduced into clinical practice and remain important first-line options for advanced NSCLC with EGFR-sensitive mutations. Gefitinib, erlotinib, and icotinib all target EGFR-sensitive mutations. Their primary differences lie in bioavailability, tissue penetration, and specific adverse effect profiles, while overall efficacy is broadly comparable.

Efficacy Characteristics

All three agents reversibly inhibit EGFR tyrosine kinase phosphorylation, blocking downstream PI3K–Akt and Ras–MAPK signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. They demonstrate clear efficacy in advanced NSCLC patients harboring EGFR exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R point mutations.

Clinical data show that as first-line therapy:

- Objective response rate (ORR): 60%–70%

- Median progression-free survival (mPFS): approximately 9–11 months

- Median overall survival (mOS): approximately 20–22 months

These agents effectively control tumor progression, alleviate tumor-related symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, and chest tightness, and delay disease deterioration.

Differences among specific agents: Erlotinib has a bioavailability of approximately 60%, slightly higher than gefitinib (approximately 59%) and icotinib (approximately 58%), and greater lipophilicity, conferring some activity against brain metastases (intracranial ORR approximately 30%–40%).

Icotinib, a first-generation EGFR-TKI developed in China, has pharmacokinetic characteristics better suited to Asian populations, with efficacy comparable to gefitinib but less fluctuation in plasma concentration.

Gefitinib is rapidly absorbed orally, with a peak concentration reached in approximately 3–7 hours, and is generally better tolerated, making it suitable for elderly or frail patients as initial therapy.

Adverse Effect Differences

Adverse effects of first-generation EGFR-TKIs primarily involve the skin and gastrointestinal systems. Overall incidence is relatively low, with grade ≥3 adverse events occurring in <10% of patients, and most events are reversible. These effects are related to mild inhibition of wild-type EGFR.

| Drug | Major Adverse Effects | Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| Gefitinib | Acneiform rash; mild diarrhea, nausea; elevated transaminases | Rash: 40%–50%; diarrhea: 20%–30%; elevated transaminases: 10%–15% |

| Erlotinib | Skin toxicity (rash, paronychia); diarrhea, nausea, vomiting; fatigue, dyspnea | Skin toxicity: 50%–60%; diarrhea: 30%–40%; nausea/vomiting: 15%–20%; fatigue/dyspnea: 10% |

| Icotinib | Acneiform rash; diarrhea; elevated transaminases | Rash: 30%–40%; diarrhea: 15%–20%; elevated transaminases: 5%–10% |

Due to their mild toxicity, confirmed efficacy, and high accessibility, first-generation EGFR-TKIs serve as foundational therapies for initial treatment of EGFR-sensitive advanced NSCLC. However, reversible binding leads to prominent resistance issues, prompting the development of second-generation EGFR-TKIs.

Second-Generation EGFR-TKIs: Afatinib and Dacomitinib — “Enhanced” Irreversible Inhibitors

Second-generation EGFR-TKIs were developed to optimize mechanisms of action by irreversibly binding to the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain and simultaneously inhibiting EGFR, HER2, and HER4.

These agents effectively suppress EGFR-sensitive mutations and delay resistance, making them suitable as first-line therapy, particularly for younger patients with high tumor burden and good performance status. However, overall toxicity is higher than that of first-generation agents, requiring careful tolerability management.

Efficacy Characteristics

Both afatinib and dacomitinib irreversibly inhibit EGFR tyrosine kinase activity, block downstream signaling, and inhibit HER2-related tumor proliferation. They demonstrate superior efficacy to first-generation agents in EGFR-sensitive mutations and are effective against certain uncommon mutations (e.g., G719X, S768I).

Clinical data indicate:

- Afatinib first-line therapy: mPFS approximately 11–13 months; ORR approximately 65%–75%

- Dacomitinib: mPFS approximately 14–15 months; ORR approximately 70%–80% (longest mPFS among first- and second-generation agents)

Dacomitinib, a pan-HER inhibitor, has broader activity, stronger blood–brain barrier penetration, and superior control of brain metastases, with particularly notable efficacy in exon 21 L858R mutations (mPFS approximately 16 months). Afatinib shows better efficacy in certain uncommon EGFR mutations.

Adverse Effect Differences

Due to irreversible binding and broad target inhibition, second-generation EGFR-TKIs are associated with higher rates of skin and gastrointestinal toxicity. Grade ≥3 adverse events occur in approximately 15%–20% of patients.

Afatinib — common adverse effects:

- Diarrhea (approximately 70%–80%), often severe; grade 3 diarrhea may occur

- Skin toxicity, mainly acneiform rash (approximately 60%–70%) and fissures, often affecting hands and feet

- Stomatitis (approximately 30%–40%)

- Paronychia (approximately 20%–30%)

- Rare interstitial lung disease (approximately 1%–2%); immediate discontinuation and medical attention are required if chest tightness or dyspnea occurs

Dacomitinib — common adverse effects:

- High incidence of skin toxicity (approximately 70%–80%), including acneiform rash and paronychia (approximately 40%–50%, significantly higher than afatinib)

- Gastrointestinal reactions such as diarrhea (approximately 60%–70%) and nausea, generally less severe than with afatinib and manageable with supportive care

- Mild hypertension (approximately 15%–20%) and fatigue (approximately 20%–30%); blood pressure monitoring is recommended, especially in elderly patients

While second-generation EGFR-TKIs improve efficacy through irreversible binding and broad target coverage, they do not address T790M resistance. Third-generation EGFR-TKIs were therefore developed to provide precise resistance control with improved safety.

Third-Generation EGFR-TKIs: Osimertinib and Aumolertinib — “Precision Rescue and First-Line Preference”

Third-generation EGFR-TKIs are central to EGFR-targeted therapy. They selectively and irreversibly inhibit EGFR-sensitive mutations and the T790M resistance mutation (present in 50%–60% of resistant cases), while sparing wild-type EGFR, resulting in lower toxicity.

They exhibit strong blood–brain barrier penetration and are suitable for patients with brain metastases. They are currently the preferred first-line therapy for EGFR-sensitive advanced NSCLC and the standard treatment after resistance to first- or second-generation TKIs in T790M-positive patients.

Efficacy Characteristics

Both agents irreversibly bind EGFR tyrosine kinase with high specificity for sensitive and T790M mutations, with <1% inhibition of wild-type EGFR. As first-line therapy:

- mPFS: 18–20 months

- mOS: 38–40 months

- ORR: 80%–85%

After resistance:

- ORR: 70%–80%

- mPFS: 11–13 months

Blood–brain barrier penetration reaches 70%–80%, with intracranial ORR >60%, providing excellent control of brain metastases.

Osimertinib has extensive clinical data and broad indications, including first- and second-line treatment and adjuvant therapy in early-stage disease (DFS approximately 90%), with slightly higher T790M inhibitory activity.

Aumolertinib is optimized for Asian metabolic characteristics, demonstrates comparable efficacy, longer first-line mPFS (19.3 months), higher ORR, stable T790M efficacy, and a more favorable safety profile; it is also applicable in adjuvant therapy.

Adverse Effect Differences

Third-generation agents have significantly lower toxicity than earlier generations, with grade ≥3 adverse events occurring in <5% of patients due to minimal inhibition of wild-type EGFR.

- Osimertinib: Common adverse effects include fatigue (20%–30%), diarrhea (15%–20%), and dry skin (10%–15%), mostly grade 1–2. Occasional hematologic toxicity (5%–10%) requires blood count monitoring. Rare interstitial lung disease, QT interval prolongation, and ocular toxicity may occur and require prompt management.

- Aumolertinib: Lower overall incidence of adverse effects than osimertinib; common events include fatigue (15%–20%) and diarrhea (10%–15%). A characteristic finding is elevated creatine kinase (20.9%–35.5%), necessitating regular monitoring; occasional transaminase elevation and rare cardiotoxicity have been reported, warranting caution in high-risk patients.

Distinct differences in mechanism, efficacy, safety, and clinical application exist among EGFR-TKI generations, with third-generation agents offering clear advantages in efficacy, safety, and resistance management, establishing well-defined clinical positioning relative to first- and second-generation therapies. This lays the foundation for subsequent analysis of the global EGFR-targeted drugs market landscape.

Global EGFR-Targeted Drugs Market Landscape and Trends

The global EGFR-targeted drugs market exhibits pronounced generational transition and regional differentiation, driven by technological innovation and clinical demand toward precision and combination strategies.

Third-generation agents (e.g., osimertinib, aumolertinib) dominate first-line therapy due to strong inhibition of resistance mutations such as T790M, with market share exceeding 88%, while first-generation agents (e.g., gefitinib) have declined to approximately 9.9% due to resistance issues.

Future trends focus on overcoming resistance through fourth-generation agents and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting mutations such as C797S, combination regimens (EGFR-TKI plus chemotherapy or immunotherapy) as first-line standards to significantly extend PFS, expanded indications for uncommon mutations and special populations (e.g., brain metastases), and early-stage interventions such as perioperative neoadjuvant therapy.

The global market size surpassed USD 70 billion in 2025, driven by innovation, regional market expansion, and broadening clinical applications.

Conclusion and Outlook

EGFR-targeted drugs have brought hope to many lung cancer patients and advanced academic progress. Compared with traditional treatments, EGFR-TKIs offer superior safety, efficacy, convenience, and reduced adverse effects, making them an effective option for patients with advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Resistance remains a key clinical challenge.

As an international pharmaceutical supplier, DengyueMed will leverage its global supply chain and collaborative R&D capabilities to support worldwide access to EGFR-targeted drugs and facilitate innovation translation, addressing resistance challenges and improving drug accessibility.

Looking ahead, the field will focus on innovative technologies such as ADCs and bispecific antibodies, advancing EGFR-targeted drugs from “precision targeting” toward “comprehensive coverage.”

FAQ About EGFR-targeted Drugs

What is an EGFR TKI?

First-line epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR TKI) therapy is the standard treatment for lung cancer patients carrying EGFR-sensitive mutations (exon 19 deletion or L858R mutation).

What was the first EGFR inhibitor?

Gefitinib and erlotinib were the first two reversible EGFR kinase inhibitors.

What is the difference between HER2 and EGFR?

Unlike EGFR, HER2 does not alter its membrane dynamics or undergo endocytosis after EGF activation; in addition, it helps retain EGFR on the cell membrane.

Which cancers express EGFR?

Related diseases:

·Endometrial cancer

·small bowel cancer

·pancreatic adenocarcinoma

·small cell lung cancer

·gastric adenocarcinoma

·nasopharyngeal carcinoma

·oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

·lung cancer